Deserts are full of two things, more than anything else: sand, and stories. Believe it or not, there are as many stories as there are grains of sand, but a story from the desert will morph, shift, and appear different day to day, just like the self-terraforming dunes. To track the changing shape of the sand, you need your eyes. To track the shifting shape of a story, you need your heart.

Here is a story not often told in the desert.

Once upon a time, there was a wolf. From when he was a cub, the wolf was known as hardheaded. See, most wolf cubs learn to play-fight by biting, pawing, and wrestling; but the desert wolf would put his head down low and charge into his opponents. He was like a living battering ram. Elder wolves watched the cub learn to fight with his head, and they said to one another, “He’d better hope he never meets a stubborn cactus.”

But the wolf never did meet a stubborn cactus, at least as a cub. In fact, the wolf grew to be a friend of the desert and its inhabitants. Many saw the wolf defending sand lizards from vultures–as the vulture swooped down, the wolf would leap up, crashing into the vulture with his big, strong skull. Many saw the wolf rolling dung with the dung beetles–sometimes, a piece of dung would grow so large from the wolf’s rolling, that a line of beetles would abandon their own dung and follow behind the wolf, singing songs of the Great Dung and the Friendly Roller.

In time, the wolf grew to be bigger and stronger than all of his brothers and sisters–than all of the wolves in the desert! He was known as a protector of many creatures, and a fierce fighter in battle, but still the elders feared that while the wolf could fight with his head, he could not think with his brain, and that this would be his downfall.

One day, while the wolves and the other creatures of the desert were basking in a particularly heated, but comfortable, sandscape, a large shape appeared in the sky. At first, it looked how the moon looks, on one of those days where you can see it during the afternoon, but it grew larger, and larger, and larger, then so large that the animals realized it was crashing (or landing?!) into the sand itself. A door opened at the front of the ship, and masked, pink soldiers marched out with their guns drawn.

The desert animals heard someone say something, but it was not in a sound they recognized–not a vulture’s caw, a wolf’s howl, or a Sara Sara Sahara’s wooble. Then: chaos. Before they knew it, the soldiers were upon them. The soldiers scooped up lizards and put them into cages; the soldiers shot down vultures from the sky; the solders stepped on beetles and buried their dung in the sand; the soldiers decided the desert was theirs, without even asking, and at the head of the attack was a big, mean man, who ate a banana and laughed at the animals’ pain.

Then, as if materializing out of the sand itself, the wolf attacked. He headbutted pigmasks, sending them flying, and broke open the cages where his desert friends had been locked up. The wolf, and his pack behind him, had rescued nearly all the animals when they noticed a trail on the ground–a trail of banana peels, leading to the big, mean man. The wolves stopped, because in Fassad’s hand was a baby wolf cub, and in his other hand was a laser gun, pointed right at its head.

The wolf howled and sprinted at Fassad, kicking up sand in its tracks. The wolf prepared itself for the biggest headbutt of its life, but then…! Where was Fassad? By taking his eyes off the man for only a split second, the wolf had lost sight of his target. How had a man of that size moved so fast? And what was that in front of the wolf now…a cactus?!

Unfortunately, like the torero and the bull, the wolf had been tricked, and it could not stop its charge. It buried its head deep into the cactus, ripping it from the ground. The animals of the desert are still not sure if the cactus’s needles embedded themselves in the wolf’s head, or if the sheer force of the headbutt was responsible for the cactus and the wolf’s permanent bonding. Some rumors say that this was not even the first time the Cactus Wolf had bonded with a cactus, but in other cases, a separation had happened not long after. Either way, because of Fassad’s side-step that day (how had he moved so fast?), the wolf became the Cactus Wolf, a chimera of animal and plant.

You’ll be happy to know, that the battle did not end there that day. See, there is a reason why Fassad calls the Cactus Wolf the “meaning thing in the desert,” for the wolf did not for a moment see its predicament as an impediment. After the pain of the chimeric combination had receded, the wolf spotted Fassad again, cowering behind some Pigmask Soldiers and still holding the baby cub, yet laughing at the same time. “Hello, Wolf!” yelled Fassad, at an ostensibly safe distance. “I see you have put on a hat! Nwehehehehe!”

That was the last time Fassad would laugh that day. The Cactus Wolf went on a tear. The legend of the battle will be passed down in the desert for years to come. It is known as, “The Howling of Many Needles.” I would reiterate it for you here, but it is a long, long battle, told in the form of a poem. I will share one of its closing images, however: Fassad, with a mustache full of sand, picking cactus needles out of every inch of his body, the claw marks of a baby cub etched along his cheek.

Later, after the battle, the Cactus Wolf’s family gathered around him and asked if he’d like the cactus removed from his head, and the Cactus Wolf said: “Now, in the moonlight, when you spot me on a dune, I will not look like you. I may not even look like a wolf, at a first glance, anymore.” He stopped for a moment, and dug his paw into the sand. “I am different now. I am desert and wolf, just short of my blood becoming sand.”

And at that, the wolf walked away.

The King of the Desert

How’s that for an origin story? I will admit, I’m not 100% happy with it. I think there are some better alternatives, but I’m not here to accurately portray the history of the desert–I’m here to impart the legends of the desert upon my readers. The story you have just read is a combination of two desert poems: “The Howling of Many Needles,” and “The Wolf Who Wanted Sand for Blood.” Both are ancient and have been passed down for many years.

If I could critique these legends, I’d say they are a little too Star Wars prequel-esque, by which I mean they answer questions we don’t need the answers to, and they’re a little too convenient (the Pigmasks being the direct cause of the Cactus Wolf, that is). See, the Cactus Wolf is probably 1,000 times cooler if it’s just a wolf with a cactus on its head–a natural chimera, a product of the environment.

That said, it’s still fun to wonder how it came to be. Was this just an unsuspecting wolf, sniffing for some water on a hot day, then one thing led to another, and a cactus got stuck on its head? Does the cactus leak water, so that the wolf never thirsts? What if a thick-footed bird would come to roost on the cactus? Would they become a chimeric trio? Why does the Cactus Wolf sleep in front of the door to the building where Fassad needs to go? Does it have a history fighting Pigmasks? Is the Cactus Wolf a lazy Pigmask creation? One of their true first chimeras? An inspiration for chimeras?

We don’t need the answers to any of these things; I just enjoy thinking about them. Writing about Mother 3, and playing it Frog by Frog, has truly brought the world to life for me. Honestly, I never gave the desert in Chapter 3 a second thought, in the same way I never really fell in love with Osohe Castle from Chapter 2. But, with a boss like the Cactus Wolf, the desert becomes fun to think about. What other creatures like this could exist out here, and what is the Pigmasks’ influence on them?

At this point, you’re probably wondering why I’m spending so much time talking about the Cactus Wolf, and the answer is simple: simplicity! Well, I guess that answer wasn’t specific, but simplicity is the key: I like the Cactus Wolf because it’s a simple design that has stuck with me over the years. It’s silly, in that it’s a wolf with a cactus on its head, but it’s memorable, in that the related boss battle is difficult, so the enemy itself makes an impression on the player. And of course, every time I talk about difficulty or impression, I understand that these two things are subjective, especially with an RPG where many players pride themselves on optimizing their gameplay, or grinding their levels, to mitigate risk. But I also try to write these blogs as if they are informed by my current play through, and by my first play through way back when. Basically, I want to write to Mother 3 veterans and Mother 3 newcomers.

When I first played Mother 3, I struggled with the Cactus Wolf. It’s a powerful enemy, and if Fassad doesn’t come to your aid, the battle can be legitmately challenging. Of course, back then, I didn’t do the Dung Sidequest for extra experience points, so that’s probably one reason why the fight was so difficult, but even with the extra levels, you’d better hope Fassad feels like fighting on the day you challenge the Cactus Wolf, because if not, Salsa’s gonna be lying next to the oasis and picking needles from his paws.

I also love how vicious the Cactus Wolf appears. At this point, the player has learned that Salsa isn’t packing much power in those monkey fists, so when an animal as mean as the Cactus Wolf steps in his way, there’s a real sense of danger that I, at least, haven’t felt since Flint encountered the Mecha Drago. Yes, the Osohe Snake was a fun fight with an awesome introduction, and Mr. Passion was challenging in his own way, but they didn’t seem as narratively or even visually threatening as the Cactus Wolf.

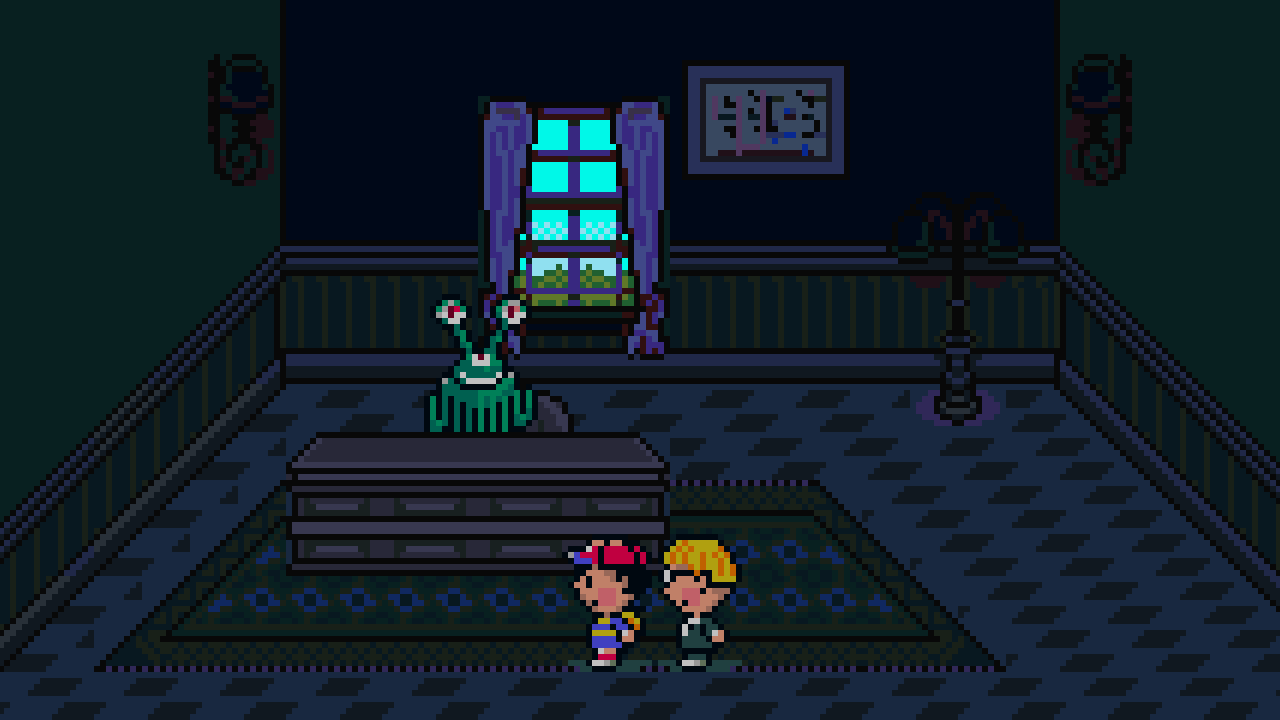

So how does everything shake out? Well, after leaving our previous frog friend behind in his cozy desert nook, Salsa and Fassad travel onward. They pass a hidden supply of dung, for the weary players who want a bit of extra experience points, then they come upon the little white house they’ve been looking for. Unfortunately for the duo, a sleeping Cactus Wolf lies in front of the door. Fassad tells Salsa that the Cactus Wolf is one of the meanest creatures in the desert, but what needs to be done must be done.

“Go beat him up,” says Fassad.

Look at that devious smolder, that piercing glare, that 170 pounds of pure, desert muscle. The Cactus Wolf is a powerful foe, fighting to the slick tune of “And El Mariachi” with the same battle sounds as the Crag Lizard–heavy electric guitar that accentuates each hit with a devestating emphasis. I hate to imagine what would happen in this battle if Fassad weren’t here, but we’ll get to that later.

Your best bet against the Cactus Wolf is, in my opinion, to use Monkey Mimic in hopes that the Cactus Wolf performs its Cactus Headbutt. Monkey Mimic will return a sizable amount of damage to the wolf, then Salsa can heal himself on the next turn. Of course, this strategy is only as useful as the number of healing items you have in your inventory, so if you’re not careful, the Cactus Wolf will eventually overcome you. What is a monkey to do?

Well, a monkey is to hope that Fassad pulls his weight in battle. Like I mentioned before, your success fighting the Cactus Wolf may be reliant on how much Fassad is willing to contribute to the fight, and, in my case, that happened to be a lot. Now, I’ve fought this battle a number of times–when I play Mother 3, I typically make it at least to Chapter 3–and I’ve had some unenthusiastic Fassads before. Sometimes, no matter what you do, and no matter how much you hope, Fassad will simply not help you out, and it’s up to Salsa to both keep himself alive and whittle down the Cactus Wolf’s health.

Other times, you get lucky. In my case, Fassad bum rushed the Cactus Wolf two or three times and topped off the battle by throwing a bomb for 200+ damage. I don’t know how much health the Cactus Wolf had left at that point (it’s possible that 200 damage was not necessary), but can I complain? Fassad basically won the battle for me.

In a way, I feel bad for the Cactus Wolf, especially on this play through. What began as a probably-unfair fight with a monkey, ended with human intervention, in the form of a bomb. I mean, I’m not saying the Cactus Wolf was a good opponent for Salsa–in reality, I assume Salsa’s desert adventure would have ended here. But I’m also not exactly a fan of the way Fassad ended things. It doesn’t seem fair. It doesn’t seem right. The battle text may say “The Cactus Wolf became tame,” but we can read between the fuzes of that explosion: in the story of this play through, at least, the Cactus Wolf may as well be dead.

Okay, okay, that might be needlessly dark head-canon, but that’s another reason why I love the fight with the Cactus Wolf: it truly elucidates the relationship between Fassad and Salsa, more so than the smaller fights we’ve been in so far. If you play your monkey cards right, the weaker enemies in the desert might not have been that big of a deal for you to fight with Salsa. You might even ask yourself, “Hey, why doesn’t Salsa defeat Fassad himself and run away?” But not after the Cactus Wolf fight.

See, I know Salsa is in a desperate, awful situation, but I think that’s what makes the Fassad dynamic so interesting and effective from a gameplay point of view. The very thing that binds Salsa to his captor–the threat of Fassad’s strength and his domineering control–is the very thing we, the player, are forced to rely on to get through battles. Without Fassad’s help, Salsa, and so we, would have an incredibly difficult time surviving, let alone making it out of the desert. It’s a terrible, abusive partnership, but the unique ability of video games to put the player into situations, rather than just tell us about situations, allows us to understand the dynamics of this relationship all the more vividly. And I’m not even saying my elucidation here is necessary–I just think it’s cool how all of this ultimately is communicated and manifested through gameplay.

What I mean is… Imagine for a moment that Fassad did not play any kind of role in battle. If this were the case, the threat of Fassad would exist only in cutscenes where he electrocutes Salsa–something we see, but never actually experience. Fassad also electrocutes Salsa when he goes “off the path,” but Mother 3 has always prevented players from going off its narrative rails, so, in this instance, electrocution would just be another version of ants at our feet. I’m not saying the player can’t emotionally connect with Salsa after seeing him electrocuted, and we certainly understand the circumstances of his capture through the cutscenes and the shock collar, but video games can do better than that! Video games can do more than just say, “Salsa is captured, and his situation is dire!”

That’s why I love the decision to make Fassad such a fearsome, powerful, non-playable character in battle; this shows us, lets us play within, the dynamic between captor and captive, cultivating an odd Stockholm Syndrome that only gaming can do. If we could control Fassad, the dynamic wouldn’t work the same, either; we need that distance, we need that disconnect, or the relationship between Salsa and Fassad would not be brought to life as accurately and vividly for the player. Like I said, I know the electrocution and the cutscenes with the shock collar are still effective–we all think Fassad is an asshole–but think about what is gained by seeing this dynamic represented through gameplay. Am I making sense?

Maybe Itoi can say it better than me…

Hell, maybe Itoi thirty years ago can say it better than me:

Novels are stories written entirely in type, right? Games have written information with pictures attached, but even so, the weight of the words in games is way higher. So if you were to have a character exclaim, “Oh, my word!”, a novel would contain a page that demonstrates why that person is surprised. In a game, it doesn’t work like that. If you’ve got one simple phrase like “Oh, my word!” showing up, if you want to show that line effectively you’ve got to set the stage just right. That’s because making a game means having a great deal of restrictions…

But it was because games had so many restrictions that I could reclaim the essence of storytelling that was already lost in novels. Like, okay, in games, you get surrounded by enemies and have to solve puzzles and such. You don’t need any kind of explanation because you first-handedly get excited, or angry, or whatever. We’re so glad we can do that—it’s an aspect unique to games. It allows us to intimately experience the emotions of the main character. When I say MOTHER is an RPG that draws you in even more than a book or a movie, that’s what I mean.

from Famicon Hisshou Hon, May 19, 1989

Maybe I’m just a geek, but I think it’s so cool that Itoi said this in 1989. Storytelling in video games is such a dynamic concept, and while his ideas here might seem simple to us now, or even obvious, I think it’s so special to see this idea come to fruition over time both in Itoi’s work, and in the video game industry at large. And no, I’m not saying Itoi is single-handedly responsible for the development of storytelling in video games; I’m sure plenty of people in the industry were having revelations like this throughout the late 80s and early 90s–in fact, storytelling is still being prioritized in gaming, more than ever before. Actually, wait a second, did Itoi ever talk about this again?

Yes, he did! In the Nintendo Dream interview! I’m going to just include the whole section, with the questions, because it works better as one piece. (I know I’ve included this first quote already on Frog by Frog, so please read the whole exchange):

Interviewer: Salsa’s story in Chapter 3 is pretty sad, too. The way Fassad always electrocutes Salsa creates a feeling of hatred for him.

Itoi: Hatred is really important too. In this case, it shows that there are people in the world of MOTHER 3 who hurt others out of enjoyment. Fassad doesn’t really understand the pain of others, you know? But the key is that he’s using the pain of others to accomplish things for his own benefit. No characters are really ever that bad. Character that bad can only be used as a joke.

Interviewer: And it’s also an important point that we’re playing as Salsa, isn’t it?

Itoi: During battles, there are times when Fassad appears to be a reliable ally. That evokes very complex emotions. Basically, the person who hurts you the most is the one who comes to your aid to save you from outside enemies. There’s also the feeling of, “You probably haven’t felt this feeling before, have you?” Games are really interesting because they’re able to do that. You wouldn’t be able to transfer something that evokes emotions in that way into a novel, for instance.

Interviewer: That’s true.

Itoi: Things like that are what give games depth.

from the Nintendo Dream Interview

Do you see what I mean now? “Things like that are what give games depth.” Itoi has been chewing on these concepts for a very long time. He has been experimenting with video game storytelling since he made the very first Mother game, all those years ago. My main reason for pointing this out, really, is to chart the success of Itoi’s experiments over the years, and it seems to me that Fassad and Salsa’s dynamic is definitely an evolution of these concepts, of “intimately experienc[ing] the emotions of the main character.”

Call me crazy, but I think Chapter 3 in the hands of another developer might have seen Fassad shock Salsa a few times, threaten him here or there, and call it a day; I think the Itoi Touch adds Fassad as a variable in battle, which allows for more varied outcomes and opportunities for the player to role-play, to live in the story world. I also think Itoi’s sensibilities as a writer are what allowed him this unique storytelling perspective in the design of his RPGs.

That said, who knows? Itoi has also remarked on the fact that Flint so tirelessly searches for Claus because one of his staff members, who was a parent, said they would never stop looking for a lost child. Perhaps creative successes like Fassad’s characterization were also the product of development team feedback; that said, I think some of the proof for it being Itoi’s doing, or at least Itoi’s idea, lies in the fact that he had similar ideas in the 80s. Am I the only one who just loves that connection, that through-line of an artist’s ideas? I love it!

Though you might be thinking, “But Fassad never hits Salsa in a cutscene, so why does his strength in combat matter? The threat isn’t his fists, but his shock collar. Who cares if Fassad fights?” Well, to me it matters for a few reasons. One, it makes Salsa, and the player, more than just Fassad’s captive; we are also now his benefactor, as he both protects and threatens us. Two, through the fights, we also see that Fassad is more than just a mustache-twirling villain. Fassad is at times so over-the-top that the player might not take him seriously, especially if he boasted about his alleged strength. Instead, we see him dispatch, with ease, enemies Salsa can barely scratch. Fassad threatens Salsa with death… yet at times, he is the only thing between Salsa and death. Trust me, if Fassad’s battle script screws around during the Cactus Wolf fight, you won’t be living for very long if you’re a first-time, or inexperienced, player.

Then, there’s the third reason I think it’s important that Fassad fights in battle, which goes precisely in-line with what Itoi was talking about. Like Salsa, the player may sometimes become confused and ask themselves, “Wait, Fassad just did that for me?” When Fassad throws bombs to quickly end difficult fights, when Fassad bum rushes an opponent to defeat it one hit, it can sometimes appear that he isn’t that bad. Fassad so convincingly fights alongisde us that it doesn’t take long for this delusion to work its magic.

But that’s what Itoi wants, I think. For the player to trust Fassad, for the player to experience these complex emotions surrounding him. Because seconds after any victory, moments after any potential bonding, the shock collar will trigger again, revealing what we always knew: that the villain’s aid was just a mean to an end–a cruel facade.

Now, as usual, I want to address the intentional fallacy in the room. I’m not saying Itoi sat down and planned for this to be the player’s interpretation of Chapter 3 or its characters. I’m not saying he said, “How can I use Fassad as a non-playable character in combat to add depth to his characterization and role in the story?” I’m not saying he said, “In 1989 I mentioned intimately connecting with characters… how can I do that here?” What I am saying is: Itoi, through his two decades of writing Mother games, was always conscious of how the story was being presented to the player, and how the player was connecting with it. Because of this sensibility, I think Itoi is able to access a greater potential in characters like Fassad, and actually characters like Wess as well. When Itoi puts a player in a room, he’s always thinking, “How many steps away are we from the toy box? How many steps away are we from imagination, from depth?”

Put simply: I just think Itoi’s playful, creative mind allows for dynamic, interesting interpretations of his games. I think it’s such a creative decision how, in the opening scene of Chapter 3, the player walks away hating Fassad… yet, within minutes, the player comes to rely on him. He is not controllable in battle, nor can he carry items, yet he is the one thing keeping Salsa alive. I don’t think you accidentally create that concept; I think it was born from Itoi’s story-conscious approach to development.

Anyway, as you can tell, I think Salsa and Fassad’s dynamic is one of Itoi’s biggest successes in RPG experimentation, and I don’t even think that has anything to do with the (probably) over-intellectualization I’ve outlined here. Just by itself, it is creative. Just by itself, it tells us stories without words. It tells us everything we need to know about these characters in a way that we can feel and experience. It tells us things not with images, not with words, words, but with play.

(There are two moments from the other games that I want to point out, just because I think they are similarly successful experiments in party configuration. If you’ve never played Mother or EarthBound, or don’t care to read about them, scroll down to the paragraph that begins, “Anyway, I think Fassad and Salsa…”)

In Mother, I love when Teddy, a young adult among children, boots Loid from your party to scale Mt. Itoi. No offense to Loid, but Teddy is so much more powerful, that using him in battle alongside Ninten and Ana feels so right. Teddy empowers the player, because he himself is the strongest physical fighter in the game up to that point. He is such a valuable asset who, through his damage output and survivability, shows the player how dangerous this last stretch of the game is going to be. He also fits uniquely into the themes of the game, because he is not quite a full adult, yet also not a kid–his story, like the other characters, isn’t about coming of age. The children characters all have parents, or at least one parent, who is absent, and Teddy’s parents are absent, but not for the same reasons: his parents were killed because of the alien invasion. To me, Teddy’s inclusion in the party raises the stakes of the story. Here we have someone who has been directly affected by the conflict of the plot, and he’s out for vengeance.

Later, when he is horribly injured (or killed), you really feel his loss because he contributed so much in such a short time. Teddy shows us the strength, the security, of a grown-up, but even he succumbs in the end, leaving the mission, once again, to the kids. For my money, the last three-to-five hours or so of Mother, however notoriously frustrating they are, are worth experiencing as what might be the pinnacle of storytelling on the NES. It is no wonder to me that the original Mother was so special for its time as a unique spark of creativity in the industry.

Another of my favorite party configurations is in EarthBound, when Paula is kidnapped by aliens, leaving Jeff and Ness by themselves. This happens just as you’ve hit your stride with your new trio of Ness, Paula, and Jeff, with new players especially finding an ease in the difficulty due to having three party members. Paula’s kidnapping disrupts the party’s dynamic, removing a reliable and effective source of PSI power. And, no offense to Jeff, but Jeff sometimes has no offense (ha…). As the enemies become more powerful, Jeff’s lack of PSI ups the stakes in battle, especially if the player’s inventory of tools for him to use is low; your new friend, who recently rescued you, is now a liability.

Paula’s abduction, and its difficulty spike, also makes this section of the game so much more memorable–the dark shopping center, the strange music, all of the humans gone, and only odd, threatening enemies left behind… Had Paua been involved, the mall would have been just another of EarthBound’s achievements in setting; in Paula’s absence, however, it becomes that and more: a memorable, difficult, impactful area of gameplay that solidifies our bond (and so Ness’s friendship) with Jeff.

Honestly, the only thing that I think is missing from EarthBound is a section where it’s only Ness and Poo. Ness and Jeff’s rescue mission is so much fun, one of EarthBound’s highlights in my opinion, but we don’t get that same chance to bond with Poo, especially given his absence while learning PK Starstorm. In EarthBound, Itoi may not do the same kind of storytelling through party configurations as he does in Mother 3, but he does still build character through it–or should I say, he builds the friendships of our main four children. Having this time with Jeff, and just with Jeff, helps us feel like we’ve truly made a new friend.

Anyway, I think Fassad and Salsa, and Chapter 3 in general, accomplish so much thematically through something as simple as party configurations. Later in the Chapter, Salsa joins Kumatora and Wess, and the three together are able to destroy a Pork Tank (with some help with Lucas, of course). How’s that for the power of friendship?

And even if you still dislike Chapter 3, or find Salsa’s gameplay to be boring, I hope I’ve convinced you, at least a little bit, to see the chapter as another piece in Itoi’s history of experiementation with RPGs. Itoi once lamented developers for only trying to fit more characters into a game, just for the sake of doing it and showing that they could, instead of focusing on the quality, depth, and representation of those characters. In the case of Mother 3, I think we can see that everyone plays their part, and even Salsa, who is a bit of a plot device at times… well what can we expect? He is literally a plotting device of Fassad’s making, meant only to charm the villagers and assist in a plot. His representation is consistent meta-textually, too.

Well, that was a pretty long discussion, wasn’t it? Let’s wrap up this post before the Cactus Wolf’s friends show up… by which I mean, the Saguargo Tiger and the Schlumbergera Bear.

Underneath the Desert

Time and time again, I’m fascinated by the implications of the Pigmasks’ reach and technology. In Chapter 1, I liked (yet also hated) how the Pigmasks appeared throughout the mountains of Tazmily, like spiders up in the corner of your shower. In Chapter 2, I was interested in the extent of the Pigmasks’ power, as large airships flew overhead and dropped waste product on Tazmily. Now, in Chapter 3, it appears the Pigmasks have stretched their reach underground, as winding tunnels and highways (or low-ways) snake beneath the planet.

When Salsa and Fassad enter the little white house, they are transported underground, then through an electronic gate, and into a dillapitated, yet not unimpressive, tunnel system. Wires are exposed; panels are upturned, broken, or nonexistent; and grime cakes the ground and the walls. I can’t tell if this place is old, or if the construction is a work in progress. How long did it take to build all of this? Who built all of this? Only the Pigmasks, or did they themselves find the remnants and add to it?

I don’t know that we ever get the answers to these questions, but I like this underground setting all the same. I mean, once again, does it not creep you out a little bit that, just below an expansive desert, there’s this? Maybe I read the book IT too early in life, and now as an adult I have an obsession for underground, out-of-sight lairs, but the Pigmasks never cease to press that button on my brain that freaks me out just so much. It’s kind of like if I walked down into my basement today and found a trapdoor, which led me to another basement I’d never known about.

If this place was built by the Pigmasks, they still have some work to do. Cockroaches skitter around and will actually offer you a decent fight (don’t forget that one of these killed me in Osohe), but I wasn’t really in the mood, so I used the recently acquired Bug Spray and ended the fight as quickly as I could. After fighting the Cactus Wolf, I didn’t want to subject Salsa to more combat. I felt a little bad about it, but look at the size of those things! They’re huge!

Eventually you’ll follow Salsa and Fassad to a room that looks a bit like an abandoned bus station, except instead of a bus, there’s a vehicle that Fassad calls a Pork Bean. These high-tech, high-power vehicles can zoom you across the planet much more quickly than any wagon, bike, or cart that Tazmily could muster. Or, as Fassad says, “In the blink of a Nwehe!”

Fassad tells Salsa that they’re going to take the Pork Bean to an “unbelievably uncivilized village called Tazmily.” This line jumped out at me. Maybe I’m too simple, or maybe it’s my midwestern roots showing, but outside of Tazmily’s awfully underdeveloped emotional intelligence, I never associate the peaceful village with “uncivilized.” I mean, yes, I know that one of the main parts of Mother 3 is the Pigmask Army modernizing Tazmily, but for some reason reading it described as “uncivilized” was more jarring than I expected. Fassad, and the Pigmasks, see the world so much differently than the simple Tazmilians.

That said, it’s cool to learn more of Fassad’s motivations. He even tells Salsa to use the Instant Revitilization Machine to heal his wounds after the jaunt through the desert. He adds that usually the machine would be wasted on a stupid monkey like Salsa, but for this time at least, he’s making an exception. I know Fassad’s doing, like, the bare minimum here, but I’ll take it. Itoi was right when he said that Salsa’s relationship with Fassad can create complex emotions. Maybe somewhere in Fassad’s heart, he does have sympathy for Salsa.

Though I wouldn’t bet on it. This exchange between Fassad and Salsa is once again rife with “stupid monkey” and other verbal abuse all over the place. There is even a dialogue prompt that can result in Salsa getting electrocuted if you answer “No,” which, trust me, I didn’t want to, but I’m trying to explore as many dialogue options as I can!

I’m sorry, Salsa!

And that brings us to today’s frog. I imagine Salsa pattering up to the frog slowly, not as easily trusting as the frog might hope. Fassad presses some buttons on the side of the Pork Bean and appears to be relatively distracted, so the Save Frog hops up on top of Salsa head. Before the monkey can grab it, the frog hops down, then all around, which excites Salsa into his own playful movements. The monkey mimics the frog, and the two pals hop in little circles, playing together as Fassad is distracted. Salsa cracks the biggest smile he has in a very, very long time. Or at least, what feels like a very long time.

The frog notices Fassad turning to say something, so it ceases to move and sits very still. Salsa does the same.

“Hey, stupid monkey,” Fassad says, throwing a banana peel at Salsa and eating a banana in two quick bites. “I’m going into the machine myself–the Cactus Wolf scratched me before we could finish it off. Serves it right. Nwehehehe!” Fassad’s laugh rings hollow through the underground tunnels, and the echo that returns is oddly high-pitched, almost feminine, with shrieking quality to it. What departed from Fassad as a laugh has returned as an otherworldly howl–something incongruent with the mustache’d slob. Fassad pauses for a moment, as if disturbed by his own sound, then presses the button on his remote control, shocking Salsa once again.

“Stupid monkey,” he says. His turns on his heels with unexpected flare, then heads to the machine.

And as Fassad walks away, the frog hops to Salsa once again, as if to console him. For a moment, the monkey doesn’t move… then he hops into the air, perches himself on top of the Pork Bean like a frog, and hops back down. He looks at his little frog friend as if to say, “Thank you, maybe nothing is so bad as long as a frog is around.” To which the frog says, “I haven’t had a chance to play with anyone in a very long time. Nothing is so bad as long as there’s a monkey around.”

And the two pals hop in little circles once again, until the revitilization machine beeps and Fassad steps out. Fassad calls the monkey to his side, and away he goes again.

Hi Shane,

Gotta say…you’ve made the Cactus Wolf a real bad-astronaut. I do like the idea that it isn’t a Pigmask Chimaera, since unlike them, the visual fusion of wolf and cactus seems symbiotic and cooperative, rather than patchwork and painful. It’s the difference between a Bulbasaur and a Dracovish if you get my drift.

The “Stockholm Syndrome” you described was more or less my experience having Fassad basically be the reason I won so many battles in the desert. I mentioned this last Frog, but I tried framing it as Salsa cleverly making his captivity a little a bit easier by forcing Fassad to do the work while he defends and eats mid-battle. That said, I still felt…uncomfortable both during and after my gaming session. I was supposed to hate Fassad…so what did it mean that Mother 3 positioned me to rely on him?

Eventually I realised something that, I‘m guessing, (since I’m not an expert on the subject) many abuse victims realise on their journey to escape those hurting them. That abusers put their victims in difficult situations so that they can then rescue them and trick them into giving their loyalty.

In real life, victims end up losing jobs, connections with loved ones, leisure time, etc. or are coerced/convinced into losing them by their abusers. This creates pressure for victims to stay with their abusers.

Fassad captured Salsa and made him traverse the desert. Then he saves Salsa multiple time from dangers the monkey couldn’t face alone, presumably conditioning them to rely on him.

But Salsa would be safe and happy with Samba if Fassad never entered their lives.

Damn. I thought Fassad was a great villain in Chapters 1 and 2 because of his psychological approach to villainy, appealing to the worst instincts of Tazmily’s residents. I had mixed feelings about his more comedic and obviously cruel nature in Chapter 3…but he’s still the manipulative jerk.

As always, looking forward to the next Frog.

Best regards,

Alexander

LikeLike

Yeah, honestly, I can’t help but wonder if the whole desert episode itself was just a way for Fassad to create depency in Salsa. Because why did they have to walk through the desert? Could they not have hitched a ride with the other Pigmasks, who flew off in a ship? Pigmasks land in ship around Tazmily all the time; they even fly an airship right over it. The only thing I can think of is that Fassad wanted extra time with Salsa to break him down 😦

LikeLike